- Questo articolo descrive le vie di fuga storiche per gli schiavi americani. Vedere Trasporto pubblico per i sistemi di metropolitana in senso letterale.

Il Ferrovia sotterranea è una rete di percorsi storici disparati utilizzati dagli schiavi afroamericani per sfuggire al stati Uniti e schiavitù raggiungendo la libertà in Canada o altri territori stranieri. Oggi molte delle stazioni lungo le "ferrovie" fungono da musei e monumenti commemorativi del viaggio degli ex schiavi verso nord.

Capire

- Guarda anche: Storia antica degli Stati Uniti

Dalla sua nascita come nazione indipendente nel 1776 fino allo scoppio del Guerra civile sulla questione nel 1861, gli Stati Uniti erano una nazione in cui l'istituzione della schiavitù causò aspre divisioni. Nel sud, la schiavitù era il fulcro di un'economia agricola alimentata da massicce piantagioni di cotone e altre colture ad alta intensità di manodopera. Nel frattempo, a nord laici stati come such Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey e tutto Nuova Inghilterra, dove la schiavitù era illegale e an abolizionista il movimento moralmente (ed economicamente) contrario alla schiavitù prosperò. Tra di loro c'erano quelli che venivano chiamati gli "stati di confine", che si estendevano da ovest a est attraverso il centro del paese da Missouri attraverso Kentucky, Virginia dell'ovest, Maryland e il Distretto della Colombia per Delaware, dove la schiavitù era legale ma controversa, con simpatie abolizioniste non sconosciute tra la popolazione.

A metà del XIX secolo, il fragile stallo che aveva caratterizzato le relazioni Nord-Sud nei primi decenni aveva lasciato il posto a crescenti tensioni. Un importante punto critico fu il Fugitive Slave Act del 1850, una legge federale che consentiva agli schiavi fuggiti scoperti negli stati liberi di essere ritrasportati forzatamente in schiavitù nel sud. Negli stati del Nord, che avevano già posto fine alla schiavitù all'interno dei propri confini, la nuova legge fu percepita come un enorme affronto, tanto più che tra il pubblico iniziarono a diffondersi storie di rapimenti violenti da parte di cacciatori di schiavi professionisti. Poiché la legge federale poteva essere applicata a stati altrimenti liberi nonostante le obiezioni locali, tutti gli schiavi fuggiti che raggiungevano improvvisamente gli stati del nord avevano buone ragioni per proseguire verso il Canada, dove la schiavitù era stata a lungo bandita - e vari gruppi trovarono rapidamente una motivazione, in linea di principio o credo religioso, di correre rischi sostanziali per assistere il loro esodo verso nord.

Vari percorsi sono stati utilizzati dagli schiavi neri per fuggire verso la libertà. Alcuni sono fuggiti a sud da Texas per Messico o da Florida in vari punti della caraibico, ma la stragrande maggioranza delle rotte si dirigeva a nord attraverso stati liberi in Canada o in altri territori britannici. Alcuni sono fuggiti attraverso Nuovo Brunswick per nuova Scozia (un ghetto di Africville esisteva in Halifax fino agli anni '60) ma le rotte più brevi e popolari attraversavano l'Ohio, che separava la schiavitù nel Kentucky dalla libertà attraverso Lago Erie nel Canada superiore.

Questo esodo coincide con un enorme boom speculativo nella costruzione di treni passeggeri come nuova tecnologia (la linea principale Grand Trunk da Montreal attraverso Toronto aperto nel 1856), quindi questa rete intermodale a maglie larghe ha prontamente adottato la terminologia ferroviaria. Coloro che reclutavano schiavi per cercare la libertà erano "agenti", le stazioni di nascondiglio o di riposo lungo la strada erano "stazioni" con i loro proprietari di case "capostazioni" e coloro che finanziavano gli sforzi "azionisti". I leader abolizionisti erano i "conduttori", di cui il più famoso era l'ex schiava Harriet Tubman, lodata per i suoi sforzi nel condurre trecento dal Maryland e dal Delaware attraverso Filadelfia e verso nord attraverso lo Stato di New York verso la libertà in Canada. In alcuni tratti, i "passeggeri" viaggiavano a piedi o si nascondevano in carri trainati da cavalli diretti a nord nelle buie notti invernali; in altri viaggiavano in nave o su rotaia convenzionale. I gruppi religiosi (come i quaccheri, la Società degli amici) erano prominenti nel movimento abolizionista e le canzoni popolari tra gli schiavi facevano riferimento al biblico Esodo a partire dal Egitto. In effetti, Tubman era "Mosè" e l'Orsa Maggiore e la stella polare Polare indicavano la terra promessa.

La ferrovia sotterranea ebbe vita relativamente breve: lo scoppio della guerra civile americana nel 1861 fece di gran parte degli stati di confine una zona di guerra, rendendo ancora di più il già pericoloso passaggio, eliminando in gran parte la necessità di un successivo esodo dagli stati del nord in Canada; nel 1865 la guerra era finita e la schiavitù era stata eliminata a livello nazionale. Tuttavia, è ricordato come un capitolo fondamentale della storia americana in generale e della storia afroamericana in particolare, con molte ex stazioni e altri siti conservati come musei o attrazioni storiche.

Preparare

Sebbene ci siano vari percorsi e sostanziali variazioni di distanza, l'esodo che segue il percorso di Harriet Tubman copre più di 500 miglia (800 km) dal Maryland e dal Delaware attraverso la Pennsylvania e New York fino all'Ontario, in Canada.

Storicamente, era possibile e relativamente facile per i cittadini di entrambi i paesi attraversare il confine tra Stati Uniti e Canada senza passaporto. Nel 21° secolo, questo in gran parte non è più vero; la sicurezza delle frontiere è diventata più severa nell'era successiva all'11 settembre 2001.

Oggi, i cittadini statunitensi richiedono un passaporto, una carta del passaporto degli Stati Uniti, una carta del programma Trusted Traveler o una patente di guida avanzata per tornare negli Stati Uniti dal Canada. Ulteriori requisiti si applicano ai residenti permanenti negli Stati Uniti e ai cittadini di paesi terzi; vedere gli articoli dei singoli paesi (Canada#Entra e Stati Uniti d'America#Entra) o controlla il Regole canadesi e Regole degli Stati Uniti per i documenti richiesti.

Mentre i percorsi qui descritti possono essere completati principalmente via terra, un ritratto storicamente accurato del trasporto nel transport vapore l'era troverebbe il viaggio su strada in ritardo miseramente molto indietro rispetto al ferrovie a vapore e navi che erano le meraviglie del loro giorno. Le strade, così com'erano, erano poco più che sentieri fangosi e sterrati adatti al meglio per un cavallo e un carro; era spesso più rapido navigare lungo il Costa Atlantica invece di tentare un percorso equivalente via terra. Un viaggio storicamente vero della ferrovia sotterranea sarebbe un bizzarro mix intermodale di tutto, dai carri a cavalli alle chiatte fluviali, ai primitivi treni merci, alla fuga a piedi o a nuoto attraverso il Mississippi. In alcuni punti in cui le rotte storicamente attraversavano il Grandi Laghi, non ci sono traghetti di linea oggi.

Il vari libri scritto dopo la guerra civile (come Wilbur Henry Siebert's La ferrovia sotterranea dalla schiavitù alla libertà: una storia completa) descrivono centinaia di percorsi paralleli e innumerevoli vecchie case che avrebbero potuto ospitare una "stazione" nel periodo di massimo splendore dell'esodo verso nord, ma di per sé non esiste un elenco completo di tutto. Poiché la rete operava in modo clandestino, pochi documenti contemporanei indicano con certezza quale sia stato il ruolo esatto che ogni singola figura o luogo svolgeva - se del caso - nell'era anteguerra. La maggior parte delle "stazioni" originali sono semplicemente vecchie case che assomigliano a qualsiasi altra casa dell'epoca; di quelli ancora in piedi, molti non sono più conservati in maniera storicamente accurata o sono residenze private non più aperte al viaggiatore. Un registro storico locale o nazionale può elencare una dozzina di proprietà in una singola contea, ma solo una piccola minoranza sono chiese storiche, musei, monumenti o punti di riferimento che invitano i visitatori a fare qualcosa di più che guidare e intravedere brevemente dall'esterno.

Questo articolo elenca molti dei punti salienti, ma di per sé non sarà mai completo.

Entra

I punti di accesso più comuni alla rete della Underground Railroad erano gli stati di confine che rappresentavano la divisione tra liberi e schiavi: Maryland; Virginia, compresa quella che oggi è la Virginia Occidentale; e Kentucky. Gran parte di questo territorio è facilmente raggiungibile da Washington DC.. Il viaggio di Tubman, ad esempio, inizia nella contea di Dorchester, sul on sponda orientale del Maryland e conduce verso nord attraverso Wilmington e Filadelfia.

| “ | Ci vediamo domani mattina. Sono diretto verso la terra promessa. | ” |

-Harriet Tubman | ||

Partire

Ci sono più percorsi e più punti di partenza per salire a bordo di questo treno; quelli qui elencati sono solo esempi notevoli.

Pennsylvania, Auburn e ferrovia del Niagara di Tubman

Questo percorso conduce attraverso la Pennsylvania e New York, attraverso vari siti associati alla "conduttrice" della metropolitana sotterranea Harriet Tubman (fuggita nel 1849, attiva fino al 1860) e ai suoi contemporanei. Nato schiavo in Contea di Dorchester, Maryland, Tubman è stata picchiata e frustata dai suoi padroni d'infanzia; scappò a Filadelfia nel 1849. Tornata nel Maryland per salvare la sua famiglia, alla fine guidò dozzine di altri schiavi verso la libertà, viaggiando di notte in estrema segretezza.

Maryland

Cambridge, Maryland - luogo di nascita di Tubman e punto di partenza del suo percorso - è separato da Washington, DC da Chesapeake Bay e si trova a circa 90 miglia (140 km) a sud-est della capitale attraverso gli Stati Uniti 50:

- 1 Monumento nazionale della ferrovia sotterranea di Harriet Tubman, 4068 Golden Hill Rd., Church Creek (17,2 km a sud di Cambridge tramite le strade statali 16 e 335), ☏ 1 410 221-2290. Tutti i giorni dalle 9:00 alle 17:00. Monumento nazionale di 7 ettari con un centro visitatori che contiene reperti sui primi anni di vita di Tubman e le imprese come conduttore della ferrovia sotterranea. Adiacente al Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, questo paesaggio è cambiato poco dai tempi della Underground Railroad. Gratuito.

- 2 Organizzazione Harriet Tubmanman, 424 Race St., Cambridge, ☏ 1 410 228-0401. Situato in un edificio d'epoca nel centro di Cambridge, questo museo di cimeli storici è aperto su appuntamento. C'è anche un centro comunitario annesso con una lista completa di programmi culturali ed educativi riguardanti Harriet Tubman e la Underground Railroad.

Delaware

Come descritto a Wilbur Siebert nel 1897, la porzione di Tubman's sentiero a partire dal 1 Cambridge a nord di Filadelfia sembra essere un viaggio via terra di 120 miglia (190 km) su strada via 2 East New Market e 3 collo di pioppo al confine di stato del Delaware, poi via 4 Sandtown, 5 Willow Grove, 6 Camden, 7 Dover, 8 Smirne, 9 Merlo, 10 Odessa, 11 Nuovo castello, e 12 Wilmington. Sono stati necessari altri 30 mi (48 km) per raggiungere 13 Filadelfia. La parte del percorso del Delaware è tracciata dal firmato Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Scenic Byway, dove sono evidenziati vari siti della ferrovia sotterranea.

- 3 Appoquinimink Friends Meetinghouse, 624 Main St., Odessa. Aperto per i servizi 1° e 3° Dom di ogni mese, 10:00. 1785 casa di preghiera quacchera in mattoni che fungeva da stazione della ferrovia sotterranea sotto John Hunn e Thomas Garrett. Un secondo piano aveva un pannello removibile che conduceva agli spazi sotto la grondaia; da una piccola apertura laterale a livello del suolo si accedeva ad una cantina.

- 4 [ex link morto]Old New Castle Court House, 211 Delaware St., New Castle, ☏ 1 302 323-4453. mar-sab 10:00-16:30, dom 13:30-16:30. Uno dei più antichi tribunali sopravvissuti negli Stati Uniti, costruito come luogo di incontro della prima Assemblea statale coloniale del Delaware (quando New Castle era la capitale del Delaware, 1732-1777). I conduttori della Underground Railroad Thomas Garrett e John Hunn furono processati e condannati qui nel 1848 per aver violato il Fugitive Slave Act, mandandoli in bancarotta con multe che servirono solo ad indurire i sentimenti sulla schiavitù di tutti i soggetti coinvolti. Donazione.

La linea di demarcazione tra stati schiavi e liberi era la linea Mason-Dixon:

- 5 Linea Mason-Dixon, Mercato della fattoria Mason-Dixon, 18166 Susquehanna Trail South, Shrewsbury, Pennsylvania. Un palo di cemento segna il confine tra il Maryland e la Pennsylvania a Shrewsbury, dove gli schiavi furono liberati dopo aver attraversato la Pennsylvania durante il Guerra civile americana. I proprietari dei mercati agricoli hanno storie da condividere sulle case della ferrovia sotterranea e altre fermate di schiavi tra il Maryland e la Pennsylvania. Liberi di stare in piedi e scattare una foto con il segnaposto in cemento.

Pennsylvania

Il primo stato "libero" sulla rotta, la Pennsylvania, abolì la schiavitù nel 1847.

Filadelfia, la capitale federale durante gran parte dell'era di George Washington, fu un focolaio di abolizionismo e l'Atto per l'abolizione graduale della schiavitù, approvato dal governo statale nel marzo 1780, fu il primo a vietare l'ulteriore importazione di schiavi in uno stato. Mentre una scappatoia esentava i membri del Congresso a Filadelfia, George e Martha Washington (come proprietari di schiavi) evitavano scrupolosamente di trascorrere sei mesi o più in Pennsylvania per paura di essere costretti a dare la libertà ai loro schiavi. Ona Judge, figlia di uno schiavo ereditato da Martha Washington, temeva di essere riportata con la forza in Virginia alla fine della presidenza di Washington; con l'aiuto dei neri liberi locali e degli abolizionisti fu imbarcata su una nave per New Hampshire e libertà.

Nel 1849, Henry Brown (1815-1897) sfuggì alla schiavitù della Virginia organizzando di farsi spedire in una cassa di legno agli abolizionisti di Filadelfia. Da lì si è trasferito a Inghilterra dal 1850 al 1875 per sfuggire al Fugitive Slave Act, diventando mago, uomo di spettacolo e schietto abolizionista.

- 6 Sito storico di Johnson House, 6306 Germantown Ave., Filadelfia, ☏ 1 215 438-1768. Sab 13-17 tutto l'anno, gio-ven 10-16 dal 2 febbraio al 9 giugno e dal 7 settembre al 24 novembre, lun-ven solo su appuntamento. I tour partono ogni 60 minuti ogni 15 minuti e l'ultimo tour parte alle 15:15. Ex casa sicura e taverna nell'area di Germantown, frequentata da Harriet Tubman e William Still, una delle 17 stazioni ferroviarie sotterranee della Pennsylvania elencate nella guida locale Ferrovia sotterranea: sentiero per la libertà. Still era un abolizionista afroamericano, impiegato e membro della Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. Vengono offerte visite guidate di un'ora. $8, anziani 55 $6, bambini sotto i 12 anni e meno di $4.

- 7 Belmont Mansion, 2000 Belmont Mansion Dr., Filadelfia, ☏ 1 215 878-8844. Mar-Ven 11-17, fine settimana estivi su appuntamento. Palazzo storico di Filadelfia con museo della ferrovia sotterranea. $7, studente/anziano $5.

- 8 Centro della ferrovia sotterranea Christianaa, 11 Green St., Christiana, ☏ 1 610 593-5340. Lun-ven 9:00-16:00. Nel 1851, un gruppo di 38 afroamericani locali e abolizionisti bianchi attaccò e uccise Edward Gorsuch, un proprietario di schiavi del Maryland che era arrivato in città inseguendo quattro dei suoi schiavi fuggiti, e ferì due dei suoi compagni. Sono stati accusati di tradimento per aver violato la legge sugli schiavi fuggitivi e l'Hotel Zercher è il luogo in cui si è svolto il processo. Oggi, l'ex hotel ospita un museo che racconta la storia di quella che divenne nota come la Resistenza a Christiana. Gratuito.

- 9 [collegamento morto]Museo afroamericano della Pennsylvania centrale, 119 N. 10th St., Lettura, ☏ 1 610 371-8713, fax: 1 610 371-8739. W&F 10:30-13:30, Dom chiuso, tutti gli altri giorni su appuntamento. L'ex chiesa Bethel AME a Reading era una volta una stazione della Underground Railroad, ora è un museo che racconta in dettaglio la storia della comunità nera e della Underground Railroad nella Pennsylvania centrale. $8, anziani e studenti con ID $6, bambini 5-12 $4, bambini sotto i 4 anni gratis. Visite guidate $10.

- 10 Casa e museo di William Goodridge, 123 E. Filadelfia St., York, ☏ 1 717 848-3610. Primo F di ogni mese 16-20 e su appuntamento. Nato in schiavitù nel Maryland, William C. Goodridge è diventato un importante uomo d'affari sospettato di aver nascosto schiavi fuggitivi in uno dei vagoni merci della sua Reliance Line. La sua bella casa a schiera di mattoni di due piani e mezzo alla periferia del centro di York è ora un museo dedicato alla sua storia di vita.

Mentre la Pennsylvania confina con il Canada attraverso il Lago Erie nel suo angolo più a nord-ovest, i cercatori di libertà che arrivavano dalle città orientali generalmente continuavano via terra attraverso lo Stato di New York verso il Canada. Mentre Harriet Tubman sarebbe fuggita direttamente a nord da Filadelfia, molti altri passeggeri stavano attraversando la Pennsylvania in più punti lungo la linea Mason-Dixon, dove lo stato confinava con il Maryland e una parte della Virginia (ora West Virginia). Questo ha creato molte linee parallele che portavano a nord attraverso la Pennsylvania centrale e occidentale nello Stato di New York Livello meridionale.

- 1 Fairfield Inn 1757, 15 W. Main St., Fairfield (8 miglia/13 km a ovest di Gettysburg tramite la Route 116), ☏ 1 717 642-5410. La più antica locanda a gestione continua nell'area di Gettysburg, risalente al 1757. Gli schiavi si nascondevano al terzo piano dopo essere strisciati attraverso aperture e botole. Oggi viene tagliata una finestra per rivelare dove si nascondevano gli schiavi quando la locanda era una "stazione sicura" sulla ferrovia sotterranea. $160/notte.

- 11 Vecchia prigione, 175 E. King St., Chambersburg, ☏ 1 717 264-1667. Mar-Sa (maggio-ottobre), gio-sab (tutto l'anno): 10:00-16:00, ultimo tour 15:00. Costruita nel 1818, la prigione sopravvisse a un attacco in cui Chambersburg fu bruciata dai Confederati nel 1864. Cinque sotterranei a cupola nella cantina avevano anelli nelle pareti e nei pavimenti per incatenare i prigionieri recalcitranti; queste celle potrebbero anche essere state usate segretamente per dare rifugio agli schiavi fuggiti in viaggio verso la libertà nel nord. $5, bambini dai 6 anni in su $4, famiglie $10.

- 12 Centro storico della ferrovia sotterranea di Blairsvilleville, 214 E. South Ln., Blairsville (17 miglia/27 km a sud di Indiana, Pennsylvania attraverso la Route 119), ☏ 1 724 459-0580. maggio-ottobre su appuntamento. L'edificio della seconda chiesa battista risale a oltre mezzo secolo dopo la ferrovia sotterranea - è stato costruito nel 1917 - ma è è la più antica struttura di proprietà dei neri nella città di Blairsville, e oggi funge da museo storico con due mostre relative alla schiavitù e all'emancipazione: "Freedom in the Air" racconta la storia degli abolizionisti della contea dell'Indiana e dei loro sforzi per aiutare i fuggitivi schiavi, mentre il titolo di "Un giorno nella vita di un bambino schiavizzato" è autoesplicativo.

- 13 Cimitero di Freedom Road, Freedom Rd., Loyalsock Township (2,4 km a nord di Williamsport via Market Street e Bloomingrove Road). Daniel Hughes (1804-1880) era un barcaiolo che trasportava legname da Williamsport a Havre de Grace, nel Maryland, sul ramo occidentale del fiume Susquehanna, nascondendo schiavi fuggiaschi nella stiva della sua chiatta durante il viaggio di ritorno. La sua fattoria ora è minuscola Guerra civile cimitero, l'ultimo luogo di riposo di nove soldati afroamericani. Anche se c'è un indicatore storico, questo posto (rinominato da Nigger Hollow a Freedom Road nel 1936) è piccolo e facile da perdere.

L'opzione più popolare, tuttavia, era quella di seguire la costa da Filadelfia a New York City in viaggio per Albany o Boston.

Stato di New York

Gli schiavi fuggiti si trovavano in un territorio amichevole nella parte settentrionale dello stato di New York, una delle regioni più fermamente abolizioniste del paese.

- 14 [collegamento morto]Residenza di Stephen e Harriet Myers, 194 Livingston Ave., Albany, ☏ 1 518 432-4432. Visite Lun-Ven 17-20, Sa mezzogiorno-16 o su appuntamento. Stephen Myers era un ex schiavo diventato liberto e abolizionista che era una figura centrale nelle vicende locali della Underground Railroad, e di tutte le numerose case che abitava nel quartiere di Arbor Hill ad Albany a metà del 19° secolo, questa è l'unica che è ancora esistente. La casa allora in rovina è stata salvata dalla palla da demolizione negli anni '70 e i lavori di restauro sono in corso, ma per ora i visitatori possono godersi visite guidate della casa e una piccola ma utile lista di mostre museali su Myers, il dottor Thomas Elkins e altri membri di spicco del Comitato di vigilanza degli abolizionisti di Albany. $ 10, anziani $ 8, bambini 5-12 $ 5.

Ad Albany esistevano più opzioni. I fuggitivi potrebbero continuare verso nord fino a Montreal o Québec'S Comuni dell'Est via Lake Champlain, o (più comunemente) potrebbero girare a ovest lungo il Canale Erie linea attraverso Siracusa per Oswego, Rochester, bufalo, o cascate del Niagara.

- 15 Ufficio immobiliare e fondiario di Gerrit Smith, 5304 Oxbow Rd., Peterboro (15,1 km a est di Cazenovia via County Route 28 e 25), ☏ 1 315 280-8828. Museo Sa-Do 13-17, fine maggio-fine agosto, tutti i giorni alba-tramonto. Smith fu presidente della New York Anti-Slavery Society (1836-1839) e "capo stazione" della Underground Railroad negli anni 1840 e 1850. La vasta tenuta in cui ha vissuto per tutta la vita è ora un complesso museale con mostre interne ed esterne su chi cerca la libertà, la ricchezza, la filantropia e la famiglia di Gerrit Smith e la ferrovia sotterranea.

Siracusa era una roccaforte abolizionista la cui posizione centrale ne faceva un "grande deposito centrale della Ferrovia Sotterranea" attraverso il quale passavano molti schiavi diretti alla libertà.

- 16 Monumento al salvataggio di Jerry, Clinton Square, Siracusa. Durante la convention statale del 1851 del Liberty Party contro la schiavitù, una folla inferocita di diverse centinaia di abolizionisti fece uscire di prigione lo schiavo evaso William "Jerry" Henry; da lì fu trasportato clandestinamente nella città del Messico, New York e lì nascosto finché una notte buia fu portato a bordo di una nave da trasporto britannico-canadese per il trasporto attraverso il lago Ontario a Kingston. Nove di coloro che hanno aiutato nella fuga (tra cui due ministri del culto) sono fuggiti in Canada; dei ventinove processati a Siracusa, tutti tranne uno furono assolti. La prigione non esiste più, ma c'è un monumento in Clinton Square che commemora questi eventi epocali.

In questa zona, i passeggeri in arrivo dalla Pennsylvania attraverso il Southern Tier hanno viaggiato attraverso Itaca e Cayuga Lake per unirsi alla strada principale a Auburn, una città a ovest di Siracusa sulla US 20. Harriet Tubman visse qui a partire dal 1859, stabilendo una casa per anziani.

- 17 Chiesa di San Giacomo AME Sion, 116 Cleveland Ave., Itaca, ☏ 1 607 272-4053. Lun-Sa 9-17 o su appuntamento. L'African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church fu fondata all'inizio del 1800 a New York City come propaggine della Methodist Episcopal Church per servire i parrocchiani neri che all'epoca incontravano un aperto razzismo nelle chiese esistenti. St. James, fondata nel 1836, era una stazione della ferrovia sotterranea, ospitava servizi frequentati da luminari afroamericani del XIX secolo come Harriet Tubman e Frederick Douglass, e nel 1906 ospitò un gruppo di studenti che fondarono Alpha Phi Alpha, il più antico della nazione confraternita nera ufficiale.

- 18 Harriet Tubman Home, 180 South St., Auburn, ☏ 1 315 252-2081. mar-ven 10-16, sab 10-15. Conosciuta come "Il Mosè del suo popolo", Tubman si stabilì ad Auburn dopo la guerra civile in questa modesta ma bella casa di mattoni, dove gestiva anche una casa per afroamericani anziani e indigenti. Oggi è un museo che ospita una collezione di cimeli storici. $ 4,50, anziani (60) e studenti universitari $ 3, bambini 6-17 $ 1,50.

- 19 Thompson AME Sion Church, 33 Parker St., Auburn. Chiuso per restauri. Una chiesa di Sion episcopale metodista africana dell'era del 1891 dove Harriet Tubman assisteva alle funzioni; in seguito affidò alla chiesa la suddetta Casa per Anziani da gestire dopo la sua morte.

- 20 Cimitero di Fort Hill, 19 Fort St., Auburn, ☏ 1 315 253-8132. Lun-ven 9-13. Situato su una collina che domina Auburn, questo sito fu utilizzato per i tumuli funerari dai nativi americani già nel 1100 d.C. Comprende i luoghi di sepoltura di Harriet Tubman e una varietà di altri luminari storici locali. Il sito Web include una mappa stampabile e un tour a piedi autoguidato.

La strada principale continua verso ovest verso Buffalo e le cascate del Niagara, che rimane oggi la serie di valichi più trafficata sul confine tra Ontario e New York. (Percorsi alternativi prevedevano l'attraversamento del Lago Ontario da Oswego o Rochester.)

- 21 Museo storico di Palmira, 132 Mercato San, Palmira, ☏ 1 315 597-6981. Mar-Gio 10-17 tutto l'anno, Mar-Sa 11-16 in alta stagione. Uno dei cinque musei separati nel complesso museale storico di Palmyra; ognuno presenta un aspetto diverso della vita nella vecchia Palmira. Il museo principale ospita varie mostre permanenti sulla storia locale, tra cui la Underground Railroad. $3, anziani $2, bambini sotto i 12 anni gratis.

Rochester, patria di Frederick Douglass e di uno stuolo di altri abolizionisti, offriva anche ai fuggitivi il passaggio in Canada, se fossero riusciti a raggiungere Kelsey's Landing, appena a nord delle Lower Falls del Genesee. C'erano un certo numero di rifugi in città, inclusa la casa di Douglass.

- 22 Museo e centro scientifico di Rochester, 657 East Ave., Rochester, ☏ 1 585 271-4320. lun-sab 9-17, dom 11-17. Il museo interattivo della scienza di Rochester ha una mostra semipermanente chiamata Volo verso la libertà: la ferrovia sotterranea di Rochester. Consente ai bambini di dare un'occhiata alla storia della ferrovia attraverso gli occhi di un bambino immaginario in fuga in Canada. Adulti $ 15, anziani/college $ 14, età 3-18 $ 13, sotto i 3 anni gratis.

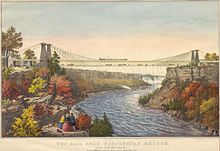

L'intero confine internazionale dell'Ontario è l'acqua. C'erano alcuni traghetti in posti come Buffalo, ma le infrastrutture erano scarse. cascate del Niagara aveva un ponte sospeso ferroviario di 825 piedi (251 m) che collegava il Canada e gli Stati Uniti. città gemelle sotto le cascate.

- 23 Museo d'Arte Castellani, 5795 Lewiston Rd., Cascate del Niagara, ☏ 1 716 286-8200, fax: 1 716 286-8289. mar-sab 11-17, dom 13-17. Parte della collezione permanente della galleria d'arte del campus della Niagara University è "Freedom Crossing: The Underground Railroad in Greater Niagara", che racconta la storia del movimento Underground Railroad sul Frontiera del Niagara.

- 24 [collegamento morto]Centro interpretativo della ferrovia sotterranea delle cascate del Niagara, 2245 Whirlpool St., Cascate del Niagara (vicino al Whirlpool Bridge e alla stazione Amtrak). Mar-M e Ven-Sa 10-18, Gio 10-20, Dom 10-16. L'ex dogana degli Stati Uniti (1863-1962) è ora un museo dedicato alla storia della ferrovia sotterranea della frontiera del Niagara. Le mostre includono una ricostruzione della "Cataract House", uno dei più grandi hotel delle Cascate del Niagara all'epoca, i cui camerieri, in gran parte afroamericani, sono stati fondamentali per aiutare gli schiavi fuggiti nell'ultima tappa del loro viaggio. $ 10, studenti delle scuole superiori e universitari con ID $ 8, bambini 6-12 $ 6.

- 25 Sito del ponte sospeso delle cascate del Niagara. Costruito nel 1848, questo primo ponte sospeso sul fiume Niagara fu l'ultima tappa del viaggio di Harriet Tubman dalla schiavitù nel Maryland alla libertà in Canada, e sarebbe tornata molte volte nel decennio successivo come "conduttrice" per altri fuggitivi. Dopo il 1855, quando fu riproposto come ponte ferroviario, gli schiavi sarebbero stati contrabbandati attraverso il confine in bovini o vagoni bagagli. Il sito è ora il Whirlpool Bridge.

A nord è Lewiston, un possibile punto di passaggio per Niagara-sul-lago in Canada:

- 26 [collegamento morto]Prima chiesa presbiteriana e cimitero del villaggio, 505 Cayuga St., Lewiston, ☏ 1 716 794-4945. Aperto per i servizi Do 11:15AM. Una scultura di fronte alla chiesa più antica di Lewiston (eretta nel 1835) commemora il ruolo di primo piano che ebbe nella Underground Railroad.

- 27 Monumento al passaggio della libertà (A Lewiston Landing Park, sul lato ovest di N. Water St. tra Center e Onondaga Sts.). Una scultura all'aperto sulla riva del fiume Niagara raffigurante il capostazione locale della ferrovia sotterranea Josiah Tryon che porta via una famiglia di cercatori di libertà nel loro ultimo approccio al Canada. Tryon gestiva la sua stazione fuori dalla Casa delle Sette Cantine, la residenza di suo fratello appena a nord del centro del villaggio (ancora esistente ma non aperta al pubblico) dove una serie di gradini conduceva da una rete a più livelli di scantinati interconnessi alla riva del fiume , da dove Tryon avrebbe traghettato i fuggitivi attraverso il fiume come raffigurato nella scultura.

A sud c'è Buffalo, di fronte Forte Erie nell'Ontario:

- 28 Chiesa Battista di Michigan Street, 511 Michigan Ave., Buffalo, ☏ 1 716 854-7976. La più antica proprietà continuamente posseduta, gestita e occupata da afroamericani a Buffalo, questa chiesa storica fungeva da stazione della ferrovia sotterranea. Si effettuano visite storiche su prenotazione. $5.

- 29 Broderick Park (sul fiume Niagara alla fine di West Ferry Street), ☏ 1 716 218-0303. Molti anni prima che il Peace Bridge fosse costruito a sud, il collegamento tra Buffalo e Fort Erie era via traghetto, e molti schiavi fuggiaschi attraversarono il fiume in Canada in questo modo. C'è un memoriale e targhe storiche in loco che illustrano il significato del sito, così come rievocazioni storiche di volta in volta.

Come accennato in precedenza, alcuni fuggitivi si sono invece avvicinati da sud, passando dalla Pennsylvania occidentale attraverso il Southern Tier verso il confine.

- 30 [ex link morto]Howe-Prescott Pioneer House, 3031 Percorso 98 Sud, Franklinville, ☏ 1 716 676-2590. dom giu-ago su appuntamento. Costruita intorno al 1814 da una famiglia di importanti abolizionisti, questa casa fungeva da stazione della ferrovia sotterranea negli anni precedenti la guerra civile. L'Ischua Valley Historical Society ha restaurato il sito come una fattoria pioniera, con mostre e dimostrazioni che illustrano la vita nei primi giorni dell'insediamento bianco nel New York occidentale.

Ontario

La fine della linea è Santa Caterina nell'Ontario Regione del Niagara.

- 31 Chiesa episcopale metodista britannica, Cappella di Salem, Via Ginevra 92, Santa Caterina, ☏ 1 905-682-0993. Servizi Dom 11:00, visite guidate su prenotazione. St. Catharines era una delle principali città canadesi ad essere colonizzata da schiavi americani fuggiti - Harriet Tubman e la sua famiglia vissero lì per circa dieci anni prima di tornare negli Stati Uniti e stabilirsi ad Auburn, New York - e questa semplice ma bella chiesa di legno era costruito nel 1851 per servire come luogo di culto. Ora è elencato come sito storico nazionale del Canada e diverse targhe sono posizionate all'esterno dell'edificio che spiegano la sua storia.

- 32 Cimitero negro, Niagara-sul-lago (lato est di Mississauga St. tra John e Mary Sts.), ☏ 1 905-468-3266. La chiesa battista del Niagara - la casa di culto della comunità di fuggitivi della ferrovia sotterranea di Niagara-on-the-Lake - è scomparsa da tempo, ma il cimitero sul suo sito precedente, dove furono sepolti molti dei suoi fedeli, rimane.

- 33 Casa del Grifone, 733 Mineral Springs Rd., Ancaster, ☏ 1 905-648-8144. Dom 13-16, luglio-settembre. Lo schiavo fuggitivo della Virginia Enerals Griffin fuggì in Canada nel 1834 e si stabilì nella città di Ancaster come agricoltore; la sua fattoria di tronchi grezzi è stata ora riportata al suo aspetto originale d'epoca. Sentieri pedonali sul retro conducono nella bella Dundas Valley e una serie di cascate. Donazione.

La regione del Niagara fa ora parte del Ferro di cavallo d'oro, la parte più densamente popolata della provincia. Più lontano, la Toronto Transit Commission (☏ 1 416-393-INFO (4636)) ha eseguito un annuale Viaggio in treno della libertà sotterranea per commemorare il Giorno dell'Emancipazione. Il treno parte dalla Union Station a centro di Toronto in tempo per raggiungere Sheppard West (l'ex capolinea nord-ovest della linea) subito dopo la mezzanotte dell'1 agosto. Le celebrazioni includono canti, letture di poesie e suonare il tamburo.

La linea dell'Ohio

Il Kentucky, uno stato schiavista, è separato dall'Indiana e dall'Ohio dal fiume Ohio. A causa della posizione dell'Ohio (che confina con il punto più meridionale del Canada attraverso il Lago Erie), più linee parallele portavano a nord attraverso lo stato verso la libertà nell'Alto Canada. Alcuni passarono dall'Indiana all'Ohio, mentre altri entrarono nell'Ohio direttamente dal Kentucky.

Indiana

Direttamente dall'altra parte del fiume da Louisville, Kentucky, la città di Nuova Albany servito come uno dei principali punti di attraversamento del fiume per i fuggitivi diretti a nord.

- 34 Chiesa dell'orologio della città, 300 E. Main St., New Albany, ☏ 1 812 945-3814. Servizi Dom 11:00, tour su prenotazione. Questa chiesa restaurata del Rinascimento greco del 1852 ospitava la Seconda Chiesa Presbiteriana, una stazione della ferrovia sotterranea la cui caratteristica torre dell'orologio segnalava la posizione di New Albany ai barcaioli del fiume Ohio. Oggi sede di una congregazione afroamericana e oggetto di raccolte fondi volte a riportare l'edificio al suo originario splendore dopo anni di abbandono, la chiesa ospita servizi regolari, visite guidate su appuntamento, rievocazioni storiche occasionali e altri eventi.

Indianapolis si trova a 130 miglia (210 km) a nord; pescatori e Westfield siamo tra i suoi sobborghi.

- 35 Museo Conner Prairie, 13400 Allisonville Rd., Fishers, ☏ 1 317 776-6000, numero verde: 1-800 966-1836. Controlla il sito web per il programma. Sede del programma teatrale-rievocazione storica "Segui la stella polare", in cui i partecipanti viaggiano indietro nell'anno 1836 e assumono il ruolo di schiavi fuggiaschi in cerca di libertà sulla ferrovia sotterranea. Impara diventando uno schiavo fuggitivo in un incontro interattivo in cui il personale del museo diventa cacciatore di schiavi, amichevoli quaccheri, schiavi liberati e conduttori ferroviari che decidono il tuo destino. $20.

Westfield è una città fantastica per escursioni a piedi; la Westfield-Washington Historical Society (vedi sotto) può fornire informazioni di base. Passeggiate e tour storici dei fantasmi dell'Indiana (☏ 1 317 840-6456) copre anche i "fantasmi della ferrovia sotterranea" in uno dei suoi tour di Westfield (prenotazione obbligatoria, controllare gli orari).

- 36 Museo e società storica di Westfield-Washington, 130 Penn St., Westfield, ☏ 1 317 804-5365. Sab 10-14, o su appuntamento. Stabilito da quaccheri fermamente abolizionisti, non dovrebbe sorprendere che Westfield fosse uno dei focolai della Underground Railroad dell'Indiana. Scopri tutto su questi e altri elementi della storia locale in questo museo. Donazione.

Dall'area di Indianapolis, il percorso si divide: puoi dirigerti a est nell'Ohio oa nord nel Michigan.

- 37 Sito storico statale di Levi e Catharine Coffin, 201 US Route 27 nord, Fountain City (9.2 miglia/14,8 km a nord di Richmond via US 27), ☏ 1 765 847-1691. Mar-Dom 10:00-17:00. The "Grand Central Station" of the Underground Railroad where three escape routes to the North converged is where Levi and Catharine Coffin lived and harbored more than 2,000 freedom seekers to safety. A family of well-to-do Quakers, the Coffins' residence is an ample Federal-style brick home that's been restored to its period appearance and opened to guided tours. A full calendar of events also take place. $10, seniors (60 ) $8, children 3-17 $5.

Another option is to head north from Kentucky directly into Ohio.

Ohio

The stations listed here form a meandering line through Ohio's major cities — Cincinnati per Dayton per Colombo per Cleveland per Toledo — and around Lake Erie to Detroit, a journey of approximately 800 mi (1,300 km). In practice, Underground Railroad passengers would head due north and cross Lake Erie at the first possible opportunity via any of multiple parallel routes.

A partire dal Lexington, Kentucky, you head north 85 mi (137 km) on this freedom train to Covington. Directly across the Ohio River and the state line is Cincinnati, one of many points at which thousands crossed into the North in search of freedom.

- 38 National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, 50 East Freedom Way, Cincinnati, ☏ 1 513 333-7500. Tu-Su 11AM-5PM. Among the most comprehensive resources of Underground Railroad-related information anywhere in the country, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center should be at the top of the list for any history buff retracing the escapees' perilous journey. The experience at this "museum of conscience" includes everything from genuine historical artifacts (including a "slave pen" built c. 1830, the only known extant one of these small log cabins once used to house slaves prior to auction) to films and theatrical performances to archival research materials, relating not only the story of the Underground Railroad but the entirety of the African-American struggle for freedom from the Colonial era through the Civil War, Jim Crow, and the modern day. $12, seniors $10, children $8.

30 mi (48 km) to the east, Williamsburg and Contea di Clermont were home to multiple stations on the Underground Railroad. 55 mi (89 km) north is Springboro, just south of Dayton in Contea di Warren.

- 39 Springboro Historical Society Museum, 110 S. Main St., Springboro, ☏ 1 937 748-0916. F-Sa 11AM-3PM. This small museum details Springboro's storied past as a vital stop on the Underground Railroad. While you're in town, stop by the Chamber of Commerce (325 S. Main St.) and pick up a brochure with a self-guided walking tour of 27 local "stations" on the Railroad, the most of any city in Ohio, many of which still stand today.

East of Dayton, one former station is now a tavern.

- 1 Ye Olde Trail Tavern, 228 Xenia Ave., Yellow Springs, ☏ 1 937 767-7448. Su-Th 11AM-10PM, F-Sa 11AM-11PM; closes an hour early Oct-Mar. Kick back with a cold beer and nosh on bar snacks with an upscale twist in this 1844 log cabin that was once a stop on the Underground Railroad. Mains $8-12.

Continue east 110 mi (180 km) through Columbus and onward to Zanesville, then detour north via Route 60.

- 40 Posto potenziale, 12150 Main St., Trinway (16 miles/26 km north of Zanesville via Route 60), ☏ 1 740 221-4175. Sa-Su noon-4PM, Mar 17-Nov 4. An ongoing historic renovation aims to bring this 29-room Italianate-style mansion back to its appearance in the 1850s and '60s, when it served as the home of railroad baron, local politico, and abolitionist George Willison Adams — not to mention one of the area's most important Underground Railroad stations. The restored portions of the mansion are open for self-guided tours (weather-dependent; the building is not air-conditioned and the upper floors can get stifling in summer, so call ahead on hot days to make sure they're open), and Prospect Place is also home to the G. W. Adams Educational Center, with a full calendar of events,

Another 110 mi (180 km) to the northeast is Alleanza.

- 41 Haines House Underground Railroad Museum, 186 W. Market St., Alliance, ☏ 1 330 829-4668. Open for tours the first weekend of each month: Sa 10AM-noon; Su 1PM-3PM. Sarah and Ridgeway Haines, daughter and son-in-law of one of the town's first settlers, operated an Underground Railroad station out of their stately Federal-style home, now fully restored and open to the public as a museum. Tour the lovely Victorian parlor, the early 19th century kitchen, the bedrooms, and the attic where fugitive slaves were hidden. Check out exhibits related to local Underground Railroad history and the preservation of the house. $3.

The next town to the north is 42 Kent, the home of Kent State University, which was a waypoint on the Underground Railroad back when the village was still named Franklin Mills. 36 mi (58 km) further north is the Lake Erie shoreline, east of Cleveland. From there, travellers had a few possible options: attempt to cross Lake Erie directly into Canada, head east through western Pennsylvania and onward to Buffalo...

- 43 Hubbard House Underground Railroad Museum, 1603 Walnut Blvd., Ashtabula, ☏ 1 440 964-8168. F-Su 1PM-5PM, Memorial Day through Labor Day, or by appointment. William and Catharine Hubbard's circa-1841 farmhouse was one of the Underground Railroad's northern termini — directly behind the house is Lake Erie, and directly across the lake is Canada — and today it's the only one that's open to the public for tours. Peruse exhibits on local Underground Railroad and Civil War history set in environs restored to their 1840s appearance, complete with authentic antique furnishings. $5, seniors $4, children 6 and over $3.

...or turn west.

- 44 Lorain Underground Railroad Station 100 Monument, 100 Black River Ln., Lorain (At Black River Landing), ☏ 1 440 328-2336. Not a station, but rather a historic monument that honors Lee Howard Dobbins, a 4-year-old escaped slave, orphaned en route to freedom with his mother, who later died in the home of the local family who took him in. A large relief sculpture, inscribed with an inspirational poem read at the child's funeral (which was attended by a thousand people), is surrounded by a contemplative garden.

West of Lorain is Sandusky, one of the foremost jumping-off points for escaped slaves on the final stage of their journey to freedom. Among those who set off across Lake Erie from here toward Canada was Josiah Henson, whose autobiography served as inspiration for Harriet Beecher Stowe's famous novel, La capanna dello zio Tom. Modern-day voyagers can retrace that journey via the MV Jiimaan[collegamento morto], a seasonal ferry plying the route from Sandusky to Leamington e Kingsville, Ontario, or else stop in to the Lake Erie Shores & Islands Welcome Center at 4424 Milan Rd. and pick up a brochure with a free self-guided walking tour of Sandusky-area Underground Railroad sites.

- 45 Maritime Museum of Sandusky, 125 Meigs St., Sandusky, ☏ 1 419 624-0274. Year-round F-Sa 10AM-4PM, Su noon-4PM; also Tu-Th 10AM-4PM Jun-Aug. This museum interprets Sandusky's prominent history as a lake port and transportation nexus through interactive exhibits and educational programs on a number of topics, including the passenger steamers whose owners were among the large number of locals active in the Underground Railroad. $6, seniors 62 and children under 12 $5, families $14.

- 46 Path to Freedom Sculpture, Facer Park, 255 E. Water St., Sandusky, ☏ 1 419 624-0274. In the center of a small harborfront park in downtown Sandusky stands this life-size sculpture of an African-American man, woman and child bounding with arms outstretched toward the waterfront and freedom, fashioned symbolically out of 800 ft (240 m) of iron chains.

As an alternative to crossing the lake here, voyagers could continue westward through Toledo to Detroit.

Michigan

Detroit was the last American stop for travellers on this route: directly across the river lies Windsor, Ontario.

- 47 First Living Museum, 33 E. Forest Ave., Detroit, ☏ 1 313 831-4080. Call museum for schedule of tours. The museum housed in the First Congregational Church of Detroit features a 90-minute "Flight to Freedom" reenactment that simulates an escape from slavery on the Underground Railroad: visitors are first shackled with wrist bands, then led to freedom by a "conductor" while hiding from bounty hunters, crossing the Ohio River to seek refuge in Levi Coffin's abolitionist safe house in Indiana, and finally arriving to "Midnight" — the code name for Detroit in Railroad parlance. $15, youth and seniors $12.

- 48 Mariners' Church, 170 E. Jefferson Ave., Detroit, ☏ 1 313 259-2206. Services Su 8:30AM & 11AM. An 1849 limestone church known primarily for serving Great Lakes sailors and memorializing crew lost at sea. In 1955, while moving the church to make room for a new civic center, workers discovered an Underground Railroad tunnel under the building.

If Detroit was "Midnight" on the Underground Railroad, Windsor was "Dawn". A literal underground railroad does stretch across the river from Detroit to Windsor, along with another one to the north between Porto Huron e Sarnia, but since 2004 the tunnels have served only freight. A ferry crosses here for large trucks only. An underground road tunnel also runs to Windsor, complete with a municipal Tunnel Bus service (C$4/person, one way).

- Gateway to Freedom International Memorial. Historians estimate that as many as 45,000 runaway slaves passed through Detroit-Windsor on the Underground Railroad, and this pair of monuments spanning both sides of the riverfront pays homage to the local citizens who defied the law to provide safety to the fugitives. Sculpted by Ed Dwight, Jr. (the first African-American accepted into the U.S. astronaut training program), the 49 Gateway to Freedom Memorial at Hart Plaza in Detroit depicts eight larger-than-life figures — including George DeBaptiste, an African-American conductor of local prominence — gazing toward the promised land of Canada. On the Windsor side, at the Civic Esplanade, the 50 Tower of Freedom depicts four more bronze figures with arms upraised in relief, backed by a 20 ft (6.1 m) marble monolith.

There is a safehouse 35 mi (56 km) north of Detroit (on the U.S. side) in Washington Township:

- 51 Loren Andrus Octagon House, 57500 Van Dyke Ave., Washington Township, ☏ 1 586 781-0084. 1-4PM on 3rd Sunday of month (Mar-Oct) or by appointment. Erected in 1860, the historic home of canal and railroad surveyor Loren Andrus served as a community meeting place and station during the latter days of the Underground Railroad, its architecture capturing attention with its unusual symmetry and serving as a metaphor for a community that bridges yesterday and tomorrow. One-hour guided tours lead through the house's restored interior and include exhibits relevant to its history. $5.

Ontario

The most period-appropriate way to replicate the crossing into Canada used to be the Bluewater Ferry across the St. Clair River between Marine City, Michigan and Sombra, Ontario. The ferry no longer operates. Instead, cross from Detroit to Windsor via the Ambassador Bridge or the aforementioned tunnel, or else detour north to the Blue Water Bridge between Port Huron and Sarnia.

- 52 Sandwich First Baptist Church, 3652 Peter St., Windsor, ☏ 1 519-252-4917. Services Su 11AM, tours by appointment. The oldest existing majority-Black church in Canada, erected in 1847 by early Underground Railroad refugees, Sandwich First Baptist was often the first Canadian stop for escapees after crossing the river from Detroit: a series of hidden tunnels and passageways led from the riverbank to the church to keep folks away from the prying eyes of slave catchers, the more daring of whom would cross the border in violation of Canadian law in pursuit of escaped slaves. Modern-day visitors can still see the trapdoor in the floor of the church.

- 1 Emancipation Day Celebration, Lanspeary Park, Windsor. Held annually on the first Saturday and Sunday in August from 2-10PM, "The Greatest Freedom Show on Earth" commemorates the Emancipation Act of 1833, which abolished slavery in Canada as well as throughout the British Empire. Live music, yummy food, and family-friendly entertainment abound. Admission free, "entertainment area" with live music $5 per person/$20 per family.

Amherstburg, just south of Windsor, was also a destination for runaway slaves.

- 53 Amherstburg Freedom Museum, 277 King St., Amherstburg, ☏ 1 519-736-5433, numero verde: 1-800-713-6336. Tu-F noon-5PM, Sa Su 1-5PM. Telling the story of the African-Canadian experience in Essex County is not only the museum itself, with a wealth of historic artifacts and educational exhibits, but also the Taylor Log Cabin, the home of an early black resident restored to its mid-19th century appearance, and also the Nazrey AME Church, a National Historic Site of Canada. A wealth of events takes place in the onsite cultural centre. Adult $7.50, seniors & students $6.50.

- 54 John Freeman Walls Historic Site and Underground Railroad Museum, 859 Puce Rd., Lakeshore (29 km/18 miles east of downtown Windsor via Highway 401), ☏ 1 519-727-6555, fax: 1 519-727-5793. Tu-Sa 10:30AM-3PM in summer, by appointment other times. Historical museum situated in the 1846 log-cabin home of John Freeman Walls, a fugitive slave from Carolina del Nord turned Underground Railroad stationmaster and pillar of the small community of Puce, Ontario (now part of the Town of Lakeshore). Dr. Bryan Walls, the museum's curator and a descendant of the owner, wrote a book entitled The Road that Leads to Somewhere detailing the history of his family and others in the community.

Following the signed African-Canadian Heritage Tour eastward from Windsor, you soon come to the so-called "Black Mecca" of Chatham, which after the Underground Railroad began quickly became — and to a certain extent remains — a bustling centre of African-Canadian life.

- 55 Chatham-Kent Museum, 75 William St. N., Chatham, ☏ 1 519-360-1998. W-F 1-7PM, Sa Su 11AM-4PM. One of the highlights of the collection at this all-purpose local history museum are some of the personal effects of American abolitionist John Brown, whose failed 1859 raid on the federal arsenal at Traghetto Harperpers, Virginia was contemporaneous with the height of the Underground Railroad era and stoked tensions on both sides of the slavery divide in the runup to the Civil War.

- 56 Black Mecca Museum, 177 King St. E., Chatham, ☏ 1 519-352-3565. M-F 10AM-3PM, till 4PM Jul-Aug. Researchers, take note: the Black Mecca Museum was founded as a home for the expansive archives of the Chatham-Kent Black Historical Society detailing Chatham's rich African-Canadian history. If that doesn't sound like your thing, there are also engaging exhibits of historic artifacts, as well as guided walking tours (call to schedule) that take in points of interest relevant to local black history. Self-guided tours free, guided tours $6.

- 57 Uncle Tom's Cabin Historic Site, 29251 Uncle Tom's Rd., Dresden (27 km/17 miles north of Chatham via County Roads 2 and 28), ☏ 1 519-683-2978. Tu-Sa 10AM-4PM, Su noon-4PM, May 19-Oct 27; also Mon 10AM-4PM Jul-Aug; Oct 28-May 18 by appointment. This sprawling open-air museum complex is centred on the restored home of Josiah Henson, a former slave turned author, abolitionist, and minister whose autobiography was the inspiration for the title character in Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel La capanna dello zio Tom. But that's not the end of the story: a restored sawmill, smokehouse, the circa-1850 Pioneer Church, and the Henson family cemetery are just some of the authentic period buildings preserved from the Dawn Settlement of former slaves. Historical artifacts, educational exhibits, multimedia presentations, and special events abound.

- 58 Buxton National Historic Site & Museum, 21975 A.D. Shadd Rd., North Buxton (16 km/10 miles south of Chatham via County Roads 2, 27, and 14), ☏ 1 519-352-4799, fax: 1 519-352-8561. Daily 10AM-4:30PM, Jul-Aug; W-Su 1PM-4:30PM, May & Sep; M-F 1PM-4:30PM, Oct-Apr. The Elgin Settlement was a haven for fugitive slaves and free blacks founded in 1849, and this museum complex — along with the annual Buxton Homecoming cultural festival in September — pays homage to the community that planted its roots here. In addition to the main museum building (containing historical exhibits) are authentic restored buildings from the former settlement: a log cabin, a barn, and a schoolhouse. $6, seniors and students $5, families $20.

Across the Land of Lincoln

Though Illinois was de jure a free state, Southern cultural influence and sympathy for the institution of slavery was very strong in its southernmost reaches (even to this day, the local culture in Cairo and other far-downstate communities bears more resemblance to the Mississippi Delta di Chicago). Thus, the fate of fugitive slaves passing through Illinois was variable: near the borders of Missouri and Kentucky the danger of being abducted and forcibly transported back to slavery was very high, while those who made it further north would notice a marked decrease in the local tolerance for slave catchers.

Il fiume Mississipi was a popular Underground Railroad route in this part of the country; a voyager travelling north from Menfi would pass between the slave-holding states of Missouri and Kentucky to arrive 175 mi (282 km) later at Cairo, a fork in the river. From there, the Mississippi continued northward through St. Louis while the Ohio River ran along the Ohio-Kentucky border to Cincinnati and beyond.

- 59 Slave Haven Underground Railroad Museum, 826 N. Second St., Memphis, Tennessee, ☏ 1 901 527-7711. Daily 10AM-4PM, till 5PM Jun-Aug. Built in 1849 by Jacob Burkle, a livestock trader and baker originally from Germania, this modest yet handsome house was long suspected to be a waypoint for Underground Railroad fugitives boarding Mississippi river boats. Now a museum, the house has been restored with period furnishings and contains interpretive exhibits. Make sure to go down into the basement, where the trap doors, tunnels and passages used to hide escaped slaves have been preserved. A three-hour historical sightseeing tour of thirty local sites is also offered for $45. $12.

Placing fugitives onto vessels on the Mississippi was a monumental risk that figured prominently in the literature of the era. There was even a "Reverse Underground Railroad" used by antebellum slave catchers to kidnap free blacks and fugitives from free states to sell them back into slavery.

Because of its location on the Mississippi River, St. Louis was directly on the boundary between slaveholding Missouri and abolitionist Illinois.

- 2 Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing, 28 E Grand Ave., St. Louis, Missouri, ☏ 1 314 584-6703. The Rev. John Berry Meachum of St. Louis' First African Baptist Church arrived in St. Louis in 1815 after purchasing his freedom from slavery. Ordered to stop holding classes in his church under an 1847 Missouri law prohibiting education of people of color, he instead circumvented the restriction by teaching on a Mississippi riverboat. His widow Mary Meachum was arrested early in the morning of May 21, 1855 with a small group of runaway slaves and their guides who were attempting to cross the Mississippi River to freedom. These events are commemorated each May with a historical reenactment of the attempted crossing by actors in period costume, along with poetry, music, dance, and dramatic performances. Even if you're not in town for the festival, you can still stop by the rest area alongside the St. Louis Riverfront Trail and take in the colorful wall mural and historic plaques.

Author Mark Twain, whose iconic novel Le avventure di Huckleberry Finn (1884) describes a freedom-seeking Mississippi voyage downriver to New Orleans, grew up in Annibale, Missouri, a short distance upriver from St. Louis. Hannibal, in turn, is not far from Quincy, Illinois, where freedom seekers would often attempt to cross the Mississippi directly.

- 60 Dr. Richard Eells House, 415 Jersey St., Quincy, ☏ 1 217 223-1800. Sa 1PM-4PM, group tours by appointment. Connecticut-born Dr. Eells was active in the abolitionist movement and is credited with helping several hundred slaves flee from Missouri. In 1842, while providing aid to a fugitive swimming the river, Dr. Eells was spotted by a posse of slave hunters. Eells escaped, but was later arrested and charged with harboring a fugitive slave. His case (with a $400 fine) was unsuccessfully appealed as far as the U.S. Supreme Court, with the final appeal made by his estate after his demise. His 1835 Greek Revival-style house, four blocks from the Mississippi, has been restored to its original appearance and contains museum exhibits regarding the Eells case in particular and the Underground Railroad in general. $3.

70 mi (110 km) east of Quincy is Jacksonville, once a major crossroads of at least three different Underground Railroad routes, many of which carried passengers fleeing from St. Louis. Several of the former stations still stand. Il Morgan County Historical Society corre a Sunday afternoon bus tour twice annually (spring and fall) from Illinois College to Woodlawn Farm with guides in period costume.

- 61 Beecher Hall, Illinois College, 1101 W. College Ave., Jacksonville, ☏ 1 217 245-3000. Founded in 1829, Illinois College was the first institution of postsecondary education in the state, and it quickly became a nexus of the local abolitionist community. The original building was renamed Beecher Hall in honor of the college's first president, Edward Beecher, brother of La capanna dello zio Tom author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Tours of the campus are offered during the summer months (see sito web for schedule); while geared toward prospective students, they're open to all and offer an introduction to the history of the college.

- 62 Woodlawn Farm, 1463 Gierkie Ln., Jacksonville, ☏ 1 217 243-5938, ✉[email protected]. W & Sa-Su 1PM-4PM, late May-late Sep, or by appointment. Pioneer settler Michael Huffaker built this handsome Greek Revival farmhouse circa 1840, and according to local tradition hid fugitive slaves there during the Underground Railroad era by disguising them as resident farmhands. Nowadays it's a living history museum where docents in period attire give guided tours of the restored interior, furnished with authentic antiques and family heirlooms. $4 suggested donation.

50 mi (80 km) further east is the state capital of 63 Springfield, the longtime home and final resting place of Abraham Lincoln. During the time of the Underground Railroad, he was a local attorney and rising star in the fledgling Republican Party who was most famous as Congressman Stephen Douglas' sparring partner in an 1858 statewide debate tour where slavery and other matters were discussed. However, Lincoln was soon catapulted from relative obscurity onto the national stage with his win in the 1860 Presidential election, going on to shepherd the nation through the Civil War and issue the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation that freed the slaves once and for all.

From Springfield, one could turn north through Bloomington and Princeton to Chicago, or continue east through Indiana to Ohio or Michigan.

- 64 Owen Lovejoy Homestead, 905 E. Peru St., Princeton (21 miles/34 km west of Perù via US 6 or I-80), ☏ 1 815 879-9151. F-Sa 1PM-4PM, May-Sep or by appointment. The Rev. Owen Lovejoy (1811-1864) was one of the most prominent abolitionists in the state of Illinois and, along with Lincoln, a founding father of the Republican Party, not to mention the brother of newspaper editor Elijah Parish Lovejoy, whose anti-slavery writings in the Alton Osservatore led to his 1837 lynching. It was more or less an open secret around Princeton that his modest farmhouse on the outskirts of town was a station on the so-called "Liberty Line" of the Underground Railroad. The house is now a city-owned museum restored to its period appearance (including the "hidey-holes" where fugitive slaves were concealed) and opened to tours in season. Onsite also is a one-room schoolhouse with exhibits that further delve into the pioneer history of the area.

- 65 Graue Mill and Museum, 3800 York Rd., Oak Brook, ☏ 1 630 655-2090. Tu-Su 10AM-4:30PM, mid Apr-mid Nov. German immigrant Frederick Graue housed fugitive slaves in the basement of his gristmill on Salt Creek, which was a favorite stopover for future President Abraham Lincoln during his travels across the state. Today, the building has been restored to its period appearance and functions as a museum where, among other exhibits, "Graue Mill and the Road to Freedom" elucidates the role played by the mill and the surrounding community in the Underground Railroad. $4.50, children 4-12 $2.

From Chicago (or points across the Wisconsin border such as Racine o Milwaukee), travel onward would be by water across the Great Lakes.

Into the Maritime Provinces

Another route, less used but still significant, led from New England through New Brunswick to Nova Scotia, mainly from Boston to Halifax. Though the modern-day Province Marittime did not become part of Canada until 1867, they were within the British Empire, and thus slavery was illegal there too.

One possible route (following the coast from Philadelphia through Boston to Halifax) would be to head north through New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts e Maine to reach New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

- 2 Wedgwood Inn, 111 W. Bridge St., New Hope, Pennsylvania, ☏ 1 215 862-2570. Situato in Contea di Bucks some 40 mi (64 km) northeast of Philadelphia, New Hope is a town whose importance on the Underground Railroad came thanks to its ferry across the Delaware River, which escaped slaves would use to pass into New Jersey on their northward journey — and this Victorian bed and breakfast was one of the stations where they'd spend the night beforehand. Of course, modern-day travellers sleep in one of eight quaintly-decorated guest rooms, but if you like, your hosts will show you the trapdoor that leads to the subterranean tunnel system where slaves once hid. Standard rooms with fireplace $120-250/night, Jacuzzi suites $200-350/night.

With its densely wooded landscape, abundant population of Quaker abolitionists, and regularly spaced towns, South Jersey was a popular east-coast Underground Railroad stopover. Swedesboro, with a sizable admixture of free black settlers to go along with the Quakers, was a particular hub.

- 66 Mount Zion AME Church, 172 Garwin Rd., Woolwich Township, New Jersey (1.5 miles/2.4 km northeast of Swedesboro via Kings Hwy.). Services Su 10:30AM. Founded by a congregation of free black settlers and still an active church today, Mount Zion was a reliable safe haven for fugitive slaves making their way from Virginia and Maryland via Philadelphia, providing them with shelter, supplies, and guidance as they continued north. Stop into this handsome 1834 clapboard church and you'll see a trapdoor in the floor of the vestibule leading to a crawl space where slaves hid.

New York City occupied a mixed role in the history of American slavery: while New York was a free state, many in the city's financial community had dealings with the southern states and Tammany Hall, the far-right political machine that effectively controlled the city Democratic Party, was notoriously sympathetic to slaveholding interests. It was a different story in what are now the outer boroughs, which were home to a thriving free black population and many churches and religious groups that held strong abolitionist beliefs.

- 67 [collegamento morto]227 Abolitionist Place, 227 Duffield St., Brooklyn, New York. In the early 19th Century, Thomas and Harriet Truesdell were among the foremost members of Brooklyn's abolitionist community, and their Duffield Street residence was a station on the Underground Railroad. The house is no longer extant, but residents of the brick rowhouse that stands on the site today discovered the trapdoors and tunnels in the basement in time to prevent the building from being demolished for a massive redevelopment project. The building is now owned by a neighborhood not-for-profit with hopes of turning it into a museum and heritage center focusing on New York City's contribution to abolitionism and the Underground Railroad; in the meantime, it plays host to a range of educational events and programs.

Nuova Inghilterra

- 68 Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, 77 Forest St., Hartford, Connecticut, ☏ 1 860 522-9258. The author of the famous antislavery novel La capanna dello zio Tom lived in this delightful Gothic-style cottage in Hartford (right next door to Mark Twain!) from 1873 until her death in 1896. The house is now a museum that not only preserves its historic interior as it appeared during Stowe's lifetime, but also offers an interactive, "non-traditional museum experience" that allows visitors to really dig deep and discuss the issues that inspired and informed her work, including women's rights, immigration, criminal justice reform, and — of course — abolitionism. There's also a research library covering topics related to 19th-century literature, arts, and social history.

- 69 Greenmanville Historic District, 75 Greenmanville Ave., Stonington, Connecticut (At the Mystic Seaport Museum), ☏ 1 860 572-5315. Tutti i giorni dalle 9:00 alle 17:00. The Greenman brothers — George, Clark, and Thomas — came in 1837 from Rhode Island to a site at the mouth of the Mystic River where they built a shipyard, and in due time a buzzing industrial village had coalesced around it. Staunch abolitionists, the Greenmans operated a station on the Underground Railroad and supported a local Seventh-Day Baptist church (c. 1851) which denounced slavery and regularly hosted speakers who supported abolitionism and women’s rights. Today, the grounds of the Mystic Seaport Museum include ten of the original buildings of the Greenmanville settlement, including the former textile mill, the church, and the Thomas Greenman House. Exhibits cover the history of the settlement and its importance to the Underground Railroad and the abolitionist movement. Museum admission $28.95, seniors $26.95, children $19.95.

- 70 Pawtuxet Village, fra Warwick e Cranston, Rhode Island. This historically preserved neighborhood represents the center of one of the oldest villages in New England, dating back to 1638. Flash forward a couple of centuries and it was a prominent stop on the Underground Railroad for runaway slaves. Walking tours of the village are available.

- 71 [collegamento morto]Jackson Homestead and Museum, 527 Washington St., Newton, Massachusetts, ☏ 1 617 796-1450. W-F 11AM-5PM, Sa-Su 10AM-5PM. This Federal-style farmhouse was built in 1809 as the home of Timothy Jackson, a Revolutionary War veteran, factory owner, state legislator, and abolitionist who operated an Underground Railroad station in it. Deeded to the City of Newton by one of his descendants, it's now a local history museum with exhibits on the local abolitionist community as well as paintings, photographs, historic artifacts, and other curiosities. $6, seniors and children 6-12 $5, students with ID $2.

Boston was a major seaport and an abolitionist stronghold. Some freedom seekers arrived overland, others as stowaways aboard coastal trading vessels from the Sud. The Boston Vigilance Committee (1841-1861), an abolitionist organization founded by the city's free black population to protect their people from abduction into slavery, spread the word when slave catchers came to town. They worked closely with Underground Railroad conductors to provide freedom seekers with transportation, shelter, medical attention and legal counsel. Hundreds of escapees stayed a short time before moving on to Canada, England or other British territories.

Il Servizio del Parco Nazionale offers a ranger-led 1.6 mi (2.6 km) Boston Black Heritage Trail tour through Boston's Beacon Hill district, near the Massachusetts State House and Boston Common. Several old houses in this district were stations on the line, but are not open to the public.

A museum is open in a former meeting house and school:

- 72 Museum of African-American History, 46 Joy St., Boston, Massachusetts, ☏ 1 617 725-0022. Lun-sab 10:00-16:00. The African Meeting House (a church built in 1806) and Abiel Smith School (the nation's oldest public school for black children, founded 1835) have been restored to the 1855 era for use as a museum and event space with exhibit galleries, education programs, caterers' kitchen and museum store.

Once in Boston, most escaped slaves boarded ships headed directly to Nova Scotia or New Brunswick. A few crossed Vermont or New Hampshire into Canada inferiore, eventually reaching Montreal...

- 73 Rokeby Museum, 4334 US Route 7, Ferrisburgh, Vermont (11 miles/18 km south of Shelburne), ☏ 1 802 877-3406. 10AM-5PM, mid-May to late Oct; house only open by scheduled guided tour. Rowland T. Robinson, a Quaker and ardent abolitionist, openly sheltered escaped slaves on his family's sheep farm in the quiet town of Ferrisburgh. Now a museum complex, visitors can tour nine historic farm buildings furnished in period style and full of interpretive exhibits covering Vermont's contribution to the Underground Railroad effort, or walk a network of hiking trails that cover more than 50 acres (20 ha) of the property. $10, seniors $9, students $8.

...while others continued to follow the coastal routes overland into Maine.

- 74 Abyssinian Meeting House, 75 Newbury St., Portland, Maine, ☏ 1 207 828-4995. Maine's oldest African-American church was erected in 1831 by a community of free blacks and headed up for many years by Reverend Amos Noé Freeman (1810-93), a known Underground Railroad agent who hosted and organized anti-slavery speakers, Negro conventions, and testimonies from runaway slaves. But by 1998, when the building was purchased from the city by a consortium of community leaders, it had fallen into disrepair. The Committee to Restore the Abyssinian plans to convert the former church to a museum dedicated to tracing the story of Maine's African-American community, and also hosts a variety of events, classes, and performances at a variety of venues around Portland.

- 75 Chamberlain Freedom Park, Corner of State and N. Main Sts., Brewer, Maine (Directly across the river from Bangor via the State Street bridge). In his day, John Holyoke — shipping magnate, factory owner, abolitionist — was one of the wealthiest citizens in the city of Brewer, Maine. When his former home was demolished in 1995 as part of a road widening project, a hand-stitched "slave-style shirt" was found tucked in the eaves of the attic along with a stone-lined tunnel in the basement leading to the bank of the Penobscot River, finally confirming the local rumors that claimed he was an Underground Railroad stationmaster. Today, there's a small park on the site, the only official Underground Railroad memorial in the state of Maine, that's centered on a statue entitled North to Freedom: a sculpted figure of an escaped slave hoisting himself out of the preserved tunnel entrance. Nearby is a statue of local Civil War hero Col. Joshua Chamberlain, for whom the park is named.

- 76 Maple Grove Friends Church, Route 1A near Up Country Rd., Fort Fairfield, Maine (9 miles/14.5 km east of Presque Isle via Route 163). 2 mi (3.2 km) from the border, this historic Quaker church was the last stop for many escaped slaves headed for freedom in New Brunswick, where a few African-Canadian communities had gathered in the Valle del fiume Saint John. Historical renovations in 1995 revealed a hiding place concealed beneath a raised platform in the main meeting room. The building was rededicated as a house of worship in 2000 and still holds occasional services.

New Brunswick and Nova Scotia

Once across the border, a few black families settled in places like Upper Kent along the Saint John River in New Brunswick. Many more continued onward to Nova Scotia, then a separate British colony but now part of Canada's Maritime Provinces.

- 3 Tomlinson Lake Hike to Freedom, Glenburn Rd., Carlingford, New Brunswick (7.2 km/4.5 miles west of Perth-Andover via Route 190). first Sa in Oct. After successfully crossing the border into New Brunswick, the first order of business for many escaped slaves on this route was to seek out the home of Sgt. William Tomlinson, a British-born lumberjack and farmer who was well known for welcoming slaves who came through this area. Every year, the fugitives' cross-border trek to Tomlinson Lake is retraced with a 2.5 km (1.6 mi) family-friendly, all-ages-and-skill-levels "hike to freedom" in the midst of the beautiful autumn foliage the region boasts. Gather at the well-signed trailhead on Glenburn Road, and at the end of the line you can sit down to a hearty traditional meal, peruse the exhibits at an Underground Railroad pop-up museum, or do some more hiking on a series of nature trails around the lake. There's even a contest for the best 1850s-period costumes. Gratuito.

- 77 sbarco del re, 5804 Route 102, Prince William, New Brunswick (40 km/25 miles west of downtown Fredericton tramite il Autostrada transcanadese), ☏ 1 506 363-4999. Daily 10AM-5PM, early June-mid Oct. Set up as a pioneer village, this living-history museum is devoted primarily to United Empire Loyalist communities in 19th century New Brunswick. However, one building, the Gordon House, is a replica of a house built by manumitted slave James Gordon in nearby Fredericton and contains exhibits relative to the Underground Railroad and the African-Canadian experience, including old runaway slave ads and quilts containing secret messages for fugitives. Onsite also is a restaurant, pub and Peddler's Market. $18, seniors $16, youth (6-15) $12.40.

Halifax, the final destination of most fugitive slaves passing out of Boston, still has a substantial mostly-black district populated by descendants of Underground Railroad passengers.

- 78 Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia, 10 Cherry Brook Rd., Dartmouth, Nova Scotia (20 km/12 miles east of downtown Halifax via Highway 111 and Trunk 7), ☏ 1 902-434-6223, numero verde: 1-800-465-0767, fax: 1 902-434-2306. M-F 10AM-4PM, also Sa noon-3PM Jun-Sep. Situated in the midst of one of Metro Halifax's largest African-Canadian neighbourhoods, the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia is a museum and cultural centre that traces the history of the Black Nova Scotian community not only during the Underground Railroad era, but before (exhibits tell the story of Black Loyalist settlers and locally-held slaves prior to the Emancipation Act of 1833) and afterward (the African-Canadian contribution to prima guerra mondiale and the destruction of Africville) as well. $6.

- 79 Africville Museum, 5795 Africville Rd., Halifax, Nova Scotia, ☏ 1 902-455-6558, fax: 1 902-455-6461. mar-sab 10:00-16:00. Africville was an African-Canadian neighbourhood that stood on the shores of Bedford Basin from the 1860s; it was condemned and destroyed a century later for bridge and industrial development. Questo museo, situato sul lato est del Seaview Memorial Park in una replica della Seaview United Baptist Church di Africville, è stato istituito come parte delle tardive scuse e restituzione del governo della città alla comunità nera di Halifax e racconta la sua storia attraverso reperti storici, fotografie e mostre interpretative che ispirano il visitatore a considerare gli effetti corrosivi del razzismo sulla società ea riconoscere la forza che deriva dalla diversità. Ogni luglio nel parco si tiene una "Riunione di Africville". $ 5,75, studenti e anziani $ 4,75, bambini sotto i 5 anni gratis.

Rimanga sicuro

Poi

Con l'approvazione del Fugitive Slave Act da parte del Congresso nel 1850, gli schiavi fuggiti negli stati del nord correvano il pericolo immediato di essere rapiti con la forza e riportati alla schiavitù del sud. I cacciatori di schiavi del sud operavano apertamente negli stati del nord, dove la loro brutalità allontanava rapidamente la gente del posto. Anche i funzionari federali erano da evitare con attenzione, poiché l'influenza dei proprietari delle piantagioni dell'allora più popoloso Sud era potente a Washington in quel momento.

Gli schiavi dovevano quindi restare nascosti durante il giorno - nascondersi, dormire o fingere di lavorare per i padroni locali - e spostarsi a nord di notte. Più a nord si facevano più lunghe e fredde quelle notti invernali. Il pericolo di incontrare agenti federali statunitensi sarebbe cessato una volta attraversato il confine canadese, ma i passeggeri della Underground Railroad avrebbero dovuto rimanere in Canada (e tenere d'occhio i cacciatori di schiavi che attraversavano il confine in violazione della legge canadese) fino alla schiavitù è stata conclusa tramite la guerra civile americana del 1860.

Anche dopo la fine della schiavitù, le lotte razziali sarebbero continuate per almeno un altro secolo e "viaggiare da neri" ha continuato a essere una proposta pericolosa. Il Libro verde dell'automobilista negro, che elencava le attività commerciali sicure per i viaggiatori afroamericani (nominalmente) a livello nazionale, sarebbe rimasto in stampa a New York dal 1936 al 1966; tuttavia, in più di poche "città del tramonto" non c'era un posto dove fermarsi per la notte per un viaggiatore di colore.

Adesso

Oggi i cacciatori di schiavi non ci sono più e le autorità federali si oppongono a varie forme di segregazione razziale nel commercio interstatale. Mentre un normale grado di cautela rimane consigliabile in questo viaggio, il principale rischio moderno è la criminalità quando si viaggia attraverso le grandi città, non la schiavitù o la segregazione.

Vai avanti

Poi

Solo una piccola minoranza di fuggitivi di successo rimase in Canada per un lungo periodo. Nonostante il fatto che la schiavitù fosse illegale lì, il razzismo e il nativismo erano un problema tanto quanto altrove. Col passare del tempo e sempre più schiavi fuggiti si riversarono attraverso il confine, iniziarono a logorare la loro accoglienza tra i canadesi bianchi. I rifugiati di solito arrivavano con solo i vestiti sulle spalle, impreparati per i rigidi inverni canadesi, e vivevano un'esistenza indigente isolati dai loro nuovi vicini. Col tempo, alcuni afro-canadesi prosperarono nell'agricoltura o negli affari e finirono per rimanere nella loro nuova casa, ma allo scoppio della guerra civile americana nel 1861, molti ex fuggitivi colsero al volo l'opportunità di unirsi all'esercito dell'Unione e svolgere un ruolo nella liberazione dei connazionali che avevano lasciato al Sud. Anche la stessa Harriet Tubman lasciò la sua casa a St. Catharines per arruolarsi come cuoca, medico e scout. Altri sono semplicemente tornati negli Stati Uniti perché erano stanchi di vivere in un luogo sconosciuto, lontano dai loro amici e dai loro cari.

Adesso